There are moments in the natural world that feel less like wildlife sightings and more like miracles — quiet reminders that survival is not only possible, but breathtaking.

That was the feeling the day a massive herd of African bush elephants gathered around a watering hole in Addo Elephant National Park. One hundred giants… and among them, about fifteen babies splashing, tumbling, trumpeting — alive in a place where their kind had almost vanished forever.

They moved like a single heartbeat, kicking up sprays of mud that glistened under the sun. Baby elephants rolled onto their sides, legs flailing, while their mothers stood nearby, patient and watchful. Every splash felt like a celebration — a kind of joy that only exists when life has been wrestled back from the edge.

But to understand why this scene matters, you have to know where these elephants came from…

And how close they came to disappearing.

When Silence Almost Replaced Their Footsteps

Three centuries ago, when the first European ships anchored at the Cape of Good Hope, thousands of elephants roamed freely across what is now South Africa. Their migration routes stretched beyond the horizon, an ancient rhythm older than any map.

But ivory — that single word — became their undoing.

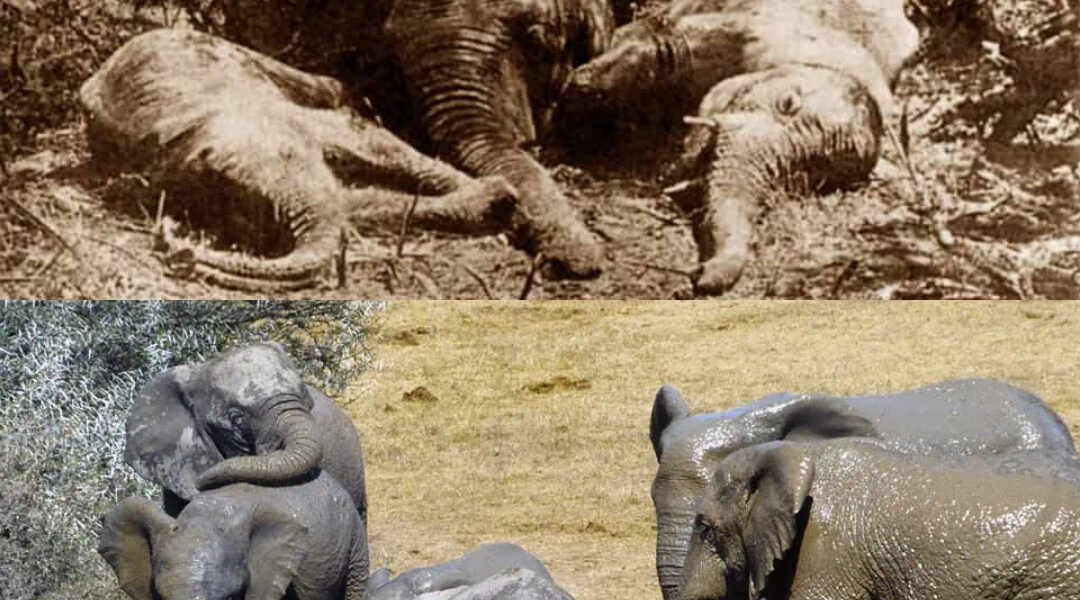

For hundreds of years, hunters carved through the herds, one tusk at a time. The killing was relentless, methodical, and monstrously efficient. By the late 1800s, the elephants of the Eastern Cape were nearly gone. Families were shattered. Trails that had echoed for centuries grew silent.

And then came the final blow.

In 1918, after elephants began raiding local orchards — not out of aggression but starvation — farmers petitioned the government to eliminate the remaining herd. Professional hunters were hired. The massacre was swift and devastating.

When the guns finally fell quiet, only thirteen elephants were left.

Thirteen.

A species once numbering in the thousands, scattered across the Cape like living mountains, had been reduced to a trembling handful hiding in thick brush, fleeing anything that moved.

But fate had not abandoned them.

Humans had nearly destroyed them — but humans would also become the ones to save them.

The Sanctuary That Became Their Second Chance

In the years that followed, those thirteen survivors were placed under protection, and Addo Elephant National Park was born — not as a tourist site, not as a park, but as a refuge. A promise.

For decades, rangers guarded those elephants around the clock. Researchers studied their movements, their genetics, their dwindling bloodlines. Conservationists fought to widen their habitat. Slowly, painfully, the herd began to stabilize.

Then, it began to grow.

From thirteen survivors…

To fifty.

To a hundred.

To the thriving, thundering community seen today.

Their comeback wasn’t luck — it was resilience. Elephants do not quit. They do not forget. They rebuild in the same steady way they live: together.

And that togetherness was on full display the day the mud bath became a celebration.

Where the Babies Learned Joy Again

On that day, photographer Nic van Oudtshoorn stood two hundred yards away with a telephoto lens. Even from that distance, he could hear everything — the trumpeting, the splashing, the deep belly rumbles that elephants use to speak to one another.

The adults waded into the mud first, churning the water until it softened into the silky brown mixture elephants crave. Then came the little ones — awkward, clumsy, endlessly enthusiastic.

One calf charged into the water too fast and toppled headfirst into the mud. For a moment, he lay there stunned.

Then came a low rumble — a mother calling.

Two adults stepped in, sliding their trunks beneath the calf’s belly, lifting him gently back to his feet. The moment he stood, he squealed — a sound of pure childish delight — and immediately charged back in.

The herd laughed in its own ancient language.

Mud baths aren’t just play.

They cool the elephants’ bodies under the ruthless African sun.

They soothe their sensitive skin.

They protect them from insects.

They teach babies how to regulate heat, how to move, how to trust.

In that mud, calves learn how to be elephants — not frightened survivors, but joyful ones.

And for a species that had once nearly lost its future, joy is a victory.

A Sound the World Almost Lost

For Nic, the sounds were unforgettable.

The trumpeting.

The rumbling chatter between mothers and calves.

The splash of water against wrinkled skin.

It wasn’t noise.

It was a choir.

A living chorus of a species that refused to disappear.

He filmed quietly, moved not by the spectacle but by the knowledge that he was witnessing something that should never have existed again — a family rebuilt from extinction’s doorstep.

“This was one of my most endearing experiences,” he said later. “To see them thriving… knowing their past… it changes you.”

And he was right.

Because if you had stood there that day, watching the herd move across the watering hole like a tide of living memory, you wouldn’t have just seen elephants.

You would have seen survival.

You would have seen healing.

You would have seen what happens when the world chooses to protect instead of destroy.

The Day the Mud Became a Monument

By the time the herd began to leave the watering hole, the babies were coated in thick, glossy mud, stumbling joyfully between the legs of their mothers.

One tiny calf struggled to climb the embankment. His legs were too short. The mud too slippery.

Before panic could rise, three adult elephants moved in. One braced the side of the hill. Another wedged her trunk beneath him. A third nudged from behind.

The baby squeaked — a sound that could melt the hardest heart.

They lifted him together.

He stood.

He wobbled.

Then he ran ahead, as if he had always known he’d be saved.

Because in an elephant herd, no one is left behind.

Not during migration.

Not during danger.

Not during play.

And not when climbing out of a mud bath that holds the memory of a century’s worth of sorrow and survival.

A Future Written in Footsteps

Today, Addo’s elephants number in the hundreds. Their genes are protected. Their land is expanding. Their story is spreading.

They are no longer ghosts in the bush.

They are no longer thirteen trembling survivors.

They are families — loud, joyful, stubborn, beautiful families — rewriting the ending that history tried to give them.

And every time a calf splashes into the mud, the world is reminded:

Some stories don’t end in extinction.

Some stories end in hope.

If we choose to let them.