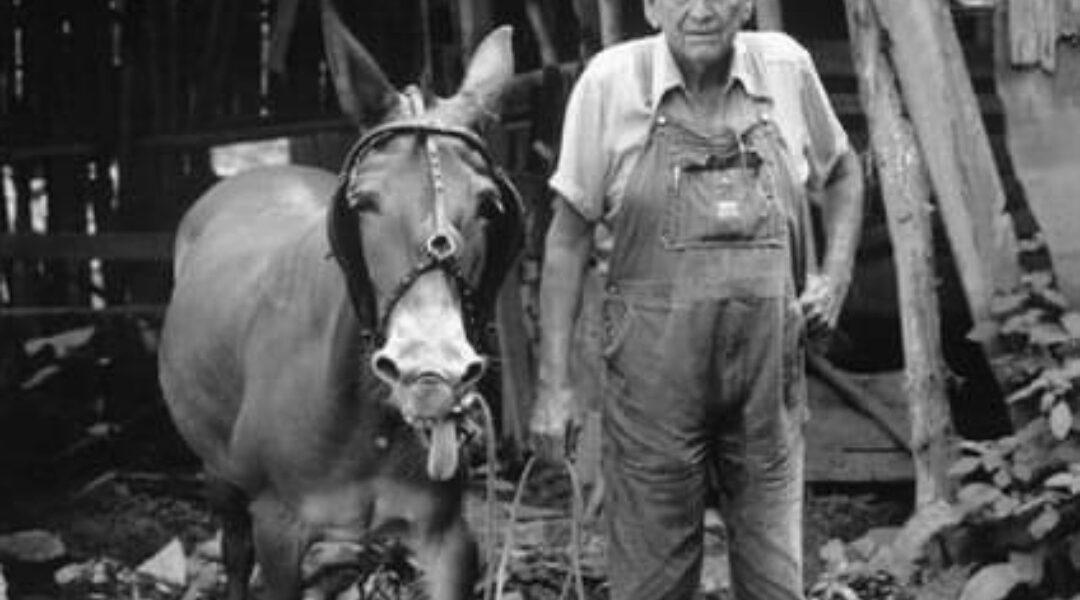

In the spring of 1940, deep within the rugged hills of Breathitt County, Kentucky, a photographer captured a simple but powerful image — a mountaineer standing beside his mule. The man’s clothes were worn, his face weathered by years of mountain wind and labor, and beside him stood the animal that had carried his world on its back.

To an outsider, it might have looked like an ordinary picture. But to anyone who has known the Appalachian hills, it was a portrait of survival — and of a partnership as old as the mountains themselves.

Life in eastern Kentucky wasn’t easy then. The land was wild and steep, carved with narrow hollows and rocky creek beds.

Roads were few, bridges scarce, and the ground so stubborn that even the most determined machines struggled to tame it. But where wagons failed and early trucks bogged down, a mule always found its footing.

For generations of mountain families, the mule was more than muscle — it was the heartbeat of the household.

When the morning fog still clung to the ridges, men hitched their mules to plows, their steady hooves breaking soil that no tractor could touch. When winter came, mules hauled timber down slick slopes, their breath steaming in the cold air.

They carried corn to the mill, coal from the mine, and even caskets to hilltop cemeteries where wheels could never go.

Every ridge, every footpath, every stubborn field bore the imprint of a mule’s hoof.

The man in the photograph — whose name has been lost to time — stands tall beside his mule, his hand resting lightly on its neck.

You can see something in his posture: pride, maybe gratitude. In those mountains, a man’s mule was often his most loyal companion, and their bond was built not from affection alone, but from shared endurance.

The mule never complained, never quit. It pulled heavy loads through knee-deep mud, climbed cliffs that would make a horse balk, and worked from dawn until dusk. In return, it was cared for like family.

Feed came before the farmer’s own supper, and when the animal fell sick, the man would sit beside it through the night.

In small communities like Berton’s Fork, along the Middle Fork of the Kentucky River, owning a mule meant independence.

It meant a family could stay on their land, haul their own firewood, and feed themselves without relying on anyone else. The mule didn’t just carry goods — it carried dignity.

By the 1940s, the world was changing fast. Machines were replacing muscle, and highways were cutting through the hills.

But in places where the land still rose too sharply for engines, the mule remained — patient, dependable, and steady as the heartbeat of Appalachia.

Today, that black-and-white photograph stands as more than a relic of a bygone era.

It’s a testament to the grit and ingenuity that defined mountain life — a life where every journey was steep, every burden heavy, and every success earned one slow, deliberate step at a time.

The mountaineer and his mule may be gone now, their names forgotten, but their story endures in the soul of the Appalachian people — a story of hard work, quiet faith, and the enduring partnership between man and beast.

Because in those hills, survival was never about power.

It was about endurance — and the courage to keep climbing.