In 1955, a tall, awkward young man with a shy smile and borrowed pants stood just outside a Broadway rehearsal room, waiting for his name to be called. The pants were too long, frayed at the hem, and didn’t quite match the jacket — but he wore them anyway. Borrowed clothing, he believed, carried borrowed luck.

Fred Gwynne was six feet six, all bones and gentleness, the kind of figure people noticed before they understood. And when he finally stepped onto the stage to audition for a role in Mrs. McThing, no one knew that the stranger in the ill-fitting suit was about to begin a journey that would make millions laugh — even as it quietly broke his own heart.

He opened his mouth, and a deep baritone — warm, rich, impossible to forget — filled the room. Halfway through the reading, one of the producers leaned in and whispered, “That’s our man.”

He got the part.

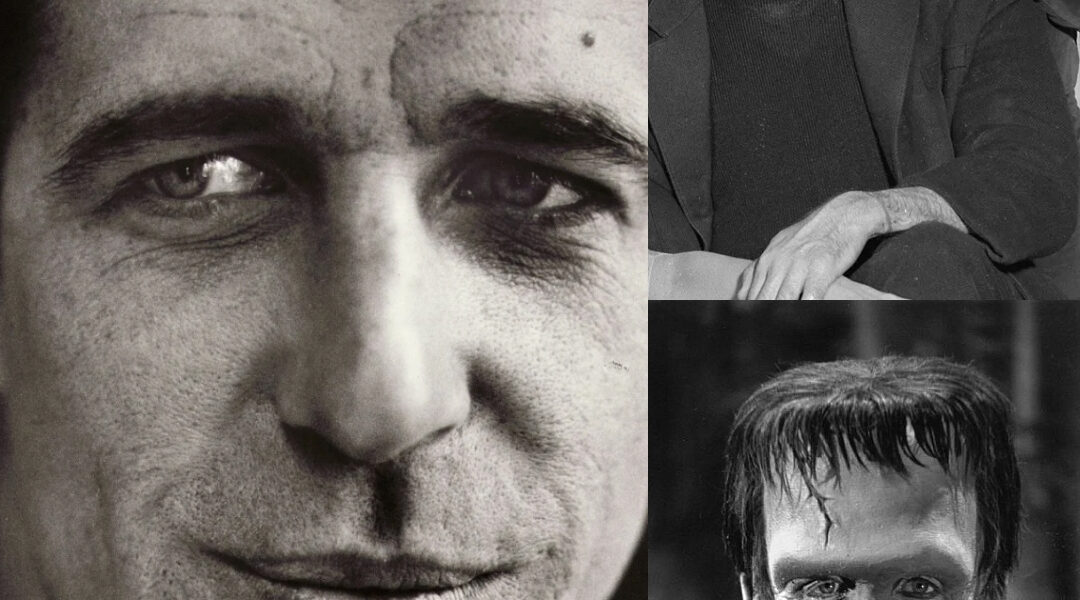

But the world didn’t yet know that the man who would one day become Herman Munster was more than a monster. Before the green makeup, before the bolts in the neck, before the booming laugh that became part of American childhood, Fred was a scholar — a Harvard graduate, an editor for The Harvard Lampoon, a singer in the Krokodiloes, a painter, a cartoonist for The New Yorker. His friends used to say, “He was the smartest funny man in any room. You’d expect jokes, but he’d give you philosophy — softly.”

His rise to fame was gentle at first. The early ’60s brought him the sitcom Car 54, Where Are You?, where America first saw the gift he carried: humor that wasn’t loud or desperate, but effortless — the kind of comedy that was kind even when it mocked.

Then, in 1964, everything changed.

The Munsters arrived, and suddenly the world knew him as Herman — the tender, towering monster with the heart of a child. Gwynne didn’t just play Herman; he protected him. He refused to make the character stupid or cruel. “Herman wasn’t silly,” he once said. “He was just trying to fit into a world that didn’t quite understand him.”

Maybe that was why the role fit too perfectly.

Millions loved him — the laugh, the softness, the innocence. But long after the show ended, the shadow of Herman Munster clung to him like a second skin. Hollywood, the town he once trusted, turned away. Casting directors would look at his tall frame, his famous face, and say, “We love you, Fred, but we can’t have Herman Munster in this role.”

He would smile politely, but it hurt — not the rejection, but the shrinking of a life into a single costume.

One afternoon in the late 1970s, he auditioned for a serious role. He read the scene flawlessly — tension, grief, restraint. The room was silent. Then the producer sighed and said, “Fred, you’re wonderful… but Herman’s sitting right there with you.”

Gwynne stood quietly, smoothed the front of his jacket, and replied, “Then let Herman leave the room.”

He walked out, not angry — just resigned. A man fighting a ghost he once helped create.

So he retreated. Not in defeat, but in redirection.

He returned to the stage, to painting, to writing books for children — books filled with wordplay and whimsical drawings, like The King Who Rained and A Chocolate Moose for Dinner. When someone asked why he wrote for children, he smiled:

“Because children understand what adults forget — that playfulness is sacred.”

He kept acting, but quietly, without the roar of cameras. He spent more time in Maryland than in California, living among trees and canvases instead of red carpets. Fame had never been a home — only a temporary address.

One afternoon in the late ’80s, a young actor approached him nervously outside a small diner. He stammered through compliments, then asked how to survive an industry that judged before it listened. Gwynne could have waved him off — but he didn’t. He pulled out a chair.

They talked for an hour.

“Don’t let the world tell you who you are,” Gwynne told him gently. “A role ends. You don’t.”

Then, as if speaking to his own reflection, he added,

“The trick is to keep creating, even when no one’s watching.”

Those who met him said he carried a kind of sadness — not bitterness, but acceptance, like a man who had learned that fame is loud, but meaning is quiet.

And then — almost like a late apology from the world — came My Cousin Vinny in 1992.

As Judge Chamberlain Haller, he didn’t shout or demand attention. He barely moved. Just one raised eyebrow, one pause before a line, and the audience roared. He wasn’t Herman — he was Fred again. Smart. Sharp. Subtle.

Hollywood called it a comeback.

Fred called it work.

He died the next year, July 2, 1993, in the same quiet way he lived the second half of his life — without spectacle. No Hollywood memorial. No televised tribute. Just a few canvases still wet with paint, a stack of children’s manuscripts, and a family that adored him.

And somewhere in attics and toy chests across America, plastic Herman Munster dolls still grinned — reminders of a man who once carried laughter like a lantern.

Near the end of his life, someone asked him what laughter meant to him. He answered with the gentleness of a man who had earned both applause and silence:

“Laughter is how I make peace with the world.”

And perhaps, in that, he finally did.

Because long after fame turned the lights away, children kept reading his books. Families kept rewatching his episodes. Strangers still smiled at the sound of that booming, joyful laugh.

The monster was never the point.

The heart behind it was.