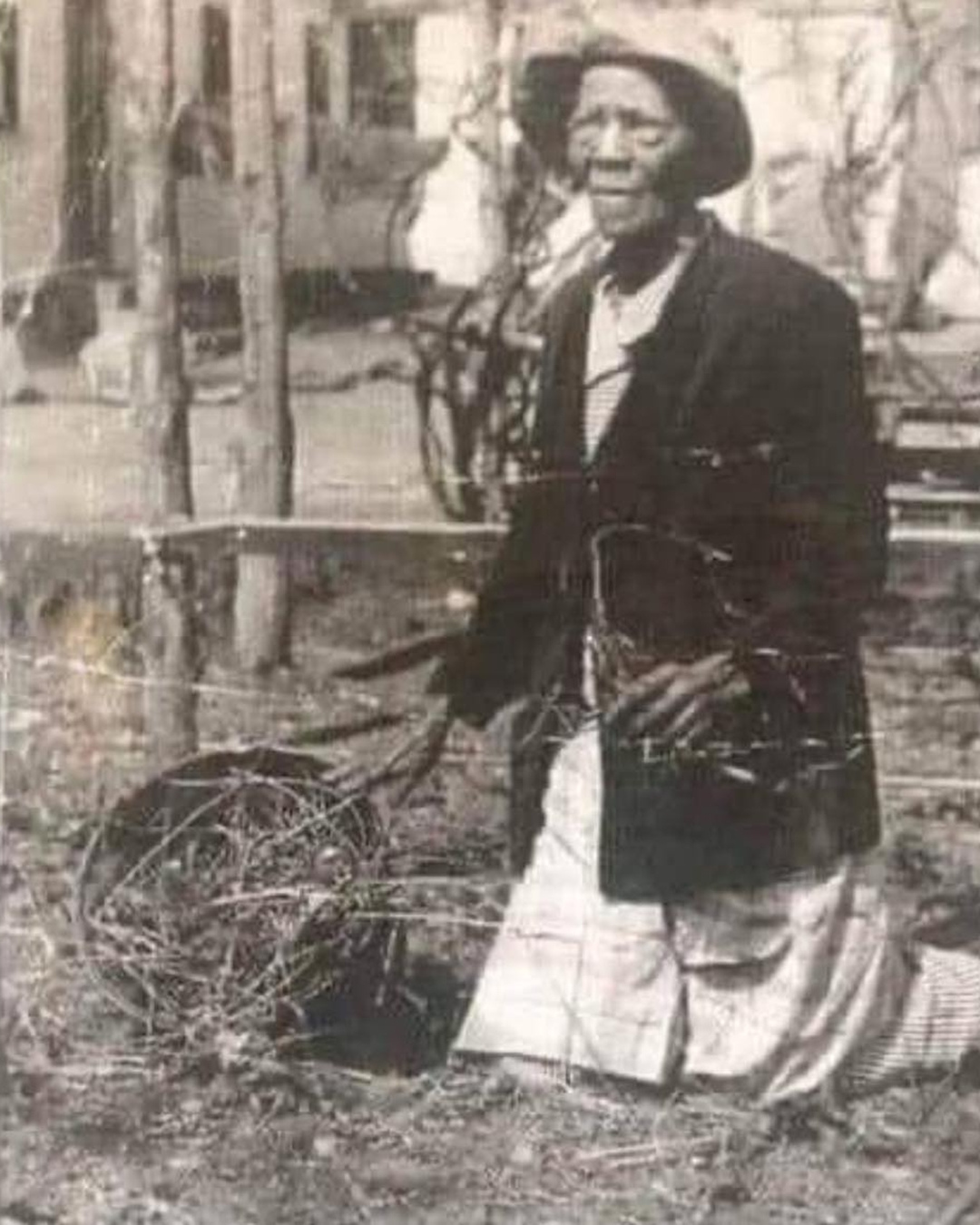

This is my great-grandmother, Christina Levant Platt. At age 100, she could still be found in her garden, bent over the earth with steady hands, pulling weeds as if time had never truly touched her. To many, she was simply an old woman with an iron spirit. To our family, she was a miracle.

Christina was born into slavery, her earliest memories shaped by the brutal rhythms of cotton fields and overseers on horseback. She lived at a time when reading and writing were forbidden to enslaved people, punishable by violence or worse. Yet, through quiet rebellion, she was given a gift that would shape the course of her life: her “owner’s” wife taught her, in secret, how to read and write.

With trembling hands, she traced letters on scraps, learning slowly but deliberately until she could open the pages of the Bible and read the words for herself. That secret education was an act of defiance, a light in the darkest of circumstances.

As a child in the fields, Christina carried water to the others working under the sun, her small frame moving carefully between rows of cotton. She was also the lookout—watching for the overseer’s horse, trained to notice the flick of its tail that signaled danger.

When she saw it, she would call out, warning her people to rise quickly from their knees where they had been praying for freedom and return to the forced labor before they were discovered. She witnessed cruelty no child should ever see.

Once, during the first battle of the Civil War at Fort Sumter in 1861, she remembered the sky blackened with cannon smoke, the earth trembling under fire. She saw a man decapitated by a cannonball—an image she carried with her for the rest of her life.

Yet Christina did not surrender to despair. She grew into a woman of deep faith and unbreakable will. She eventually married John C. Platt, a man from the Santee Tribe, and together they built a life in freedom.

Freedom, however, was not enough for her. She understood something profound: true liberation required knowledge. Education became her obsession—not for herself, but for her children. She gave birth to eleven children, losing two along the way, yet she poured every ounce of her love and determination into the ones she raised.

She sent her four boys to Boston for college—an extraordinary feat in those days, especially for a Black woman who had begun life in chains. One of her sons went on to become one of the first Black attorneys in the United States. Education was her rebellion, her victory over a system designed to keep her and her descendants in ignorance.

By the time she was widowed, she had made another radical decision: to move her family north, away from the South that still clung to its hatred. She and her husband built a home in Medfield, Massachusetts, where they became the first Black family to settle in the town. She was determined that her children would grow up in a place where opportunity, however imperfect, was possible.

Christina lived to be 101 years old, passing away in 1944. Though she died five years before I was born, I feel her presence as if I knew her. My family tells me she often said, “I put prayers on my children’s children’s heads.” I believe those prayers reached me—and they carry me still.

Whenever I thought I was enduring a hard day, I would think of her—of a little girl running water to the fields under a sky filled with cannon smoke, of a young woman standing watch to protect others at the risk of her own life, of a mother who clawed open the doors of education for her children. Compared to that, my struggles seemed so small.

She was more than a survivor. She was a builder, a protector, a visionary. She wove resilience into the very fabric of our family. Today, when I reflect on her life, I know that her story is just one among millions, but it is ours, and it is precious.

With great respect, I honor my great-grandmother, Christina Levant Platt. She showed us that even in the harshest soil, faith and determination can plant seeds that flourish for generations.