Fame had already begun to shape her life by the time she reached 30. The world adored Audrey Hepburn — the doe-eyed star with the fragile frame and the unshakable grace, a woman whose presence seemed made of silk and light. But beneath the satin gowns and diamond tiaras, Audrey remained something far simpler: a soul that wanted gentleness in a world that was not always kind.

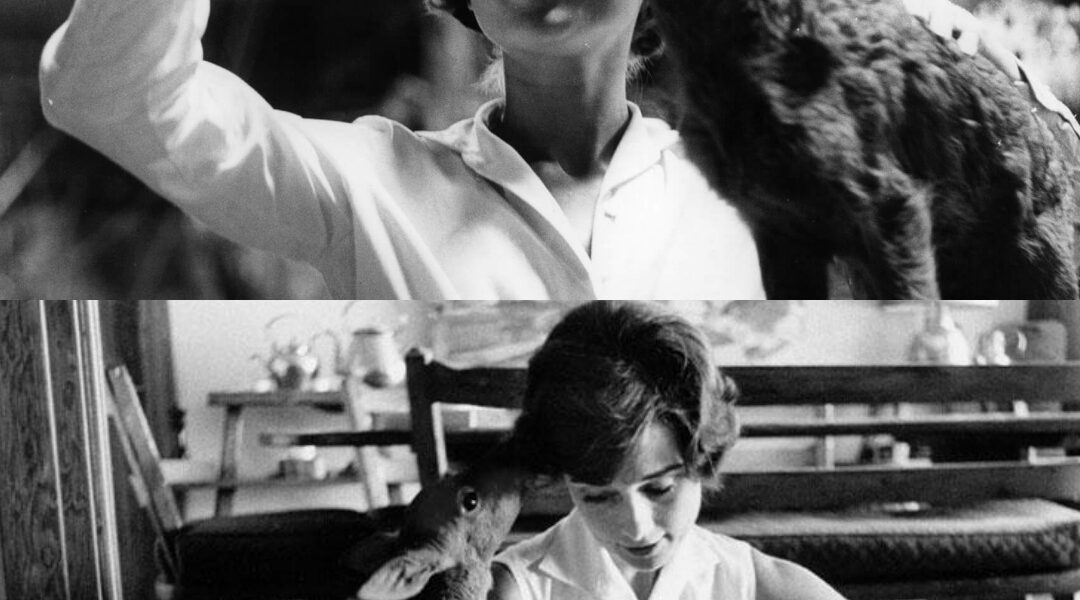

In 1959, she was cast in a film called Green Mansions, a jungle romance that paired her character with a young fawn — not a trained animal, not a CGI illusion, but a real baby deer. The animal trainer suggested Audrey rehearse with the fawn off-set so it would learn to trust her. Actors usually agreed to a few hours of handling, but Audrey did something no one expected:

She took the deer home.

She held it, fed it, learned its rhythms, and whispered to it until fear melted into familiarity. And soon, the fawn — small enough to fit in her arms — began following her not as a trainer-assigned partner, but as something closer to a child.

Audrey named it Ip.

People had always called her ethereal, but in truth it was Ip who seemed made of air. He moved like silence made visible — soft hooves, trembling legs, a heartbeat so quick it fluttered beneath Audrey’s hands like a trapped bird.

In the mornings, Ip would wake before Audrey and stand beside her bed, waiting. If she was slow to rise, he nudged her cheek gently with his nose. She would laugh — not the poised laughter that charmed photographers, but something warmer, something unguarded.

“Good morning, darling,” she would whisper, and the deer would follow her into the kitchen, standing close enough for its fur to brush against her nightgown.

Audrey prepared her breakfast, and a small bowl for Ip — mashed grains, softened leaves, and bits of fruit. He watched her every movement, as if memorizing the choreography of a mother.

And every time she left a room, he trailed after her, never more than a step behind.

Not a pet.

Not a prop.

Something else entirely.

Ip went everywhere Audrey went — not just through her home, but out into the world.

People in Beverly Hills were stunned to see her shopping with a deer walking obediently beside her, its tiny hooves tapping against grocery store tiles. It drew stares, gasps, laughter. But Audrey walked as if the sight were entirely ordinary, her hand resting lightly on Ip’s head, her posture calm, almost protective.

A friend once said, “Audrey walked as though nothing was unusual — as if the world should have expected to see her with a deer trotting loyally behind her.”

And maybe that was the truth: Audrey made the impossible look natural.

She always had.

But the bond between Audrey and Ip wasn’t born from whimsy or glamour.

It came from a wound.

As a child in war-torn Holland, Audrey had starved. Not metaphorically — literally. She had eaten tulip bulbs to survive. She had watched fear replace childhood. She had seen innocence crushed under rationing, gunfire, occupation. She was 11 years old when the Nazis took her uncle and executed him. She was 14 when she watched trains full of Jewish children disappear forever.

No red carpet could erase the memory of hunger.

No applause could replace the safety she never had.

So when Ip arrived — small, frightened, dependent — something in Audrey recognized herself.

A creature too gentle for the world.

A life that needed protection.

To care for him wasn’t indulgence.

It was recovery.

A crew member later said:

“Ip trusted her completely. It was as though Audrey gave him her heart.”

But the truth may have been the reverse.

There were moments at home when the mask of Audrey Hepburn — the star, the icon, the immaculate swan — slipped away. Moments when she sat cross-legged on the floor, hair unbrushed, dress wrinkled, and held Ip in her lap the way a mother holds a newborn, breathing in its warmth.

Sometimes she cried. Not loudly. Not dramatically. Just silent tears that softened against the animal’s fur.

She would stroke his head and say quietly, almost like prayer:

“You’re safe here. No one will hurt you.”

It was a promise she once wished someone had made to her.

At night, Ip slept beside her. He curled against her body the way a child curls into its mother, trusting that the world outside the shared warmth could wait until morning. His small head rested against her shoulder, and Audrey would fall asleep with one arm draped over him.

The world adored Audrey because she was beautiful.

But Ip adored her because she was kind.

The bond never fully ended, even after filming was done. Ip eventually grew too large to live inside a house, and arrangements were made for him to live safely on a ranch not far from Audrey’s home. She visited often — always with treats, always with the same soft voice.

And while the film Green Mansions faded in history — a movie few remember — the photographs did not fade.

The image of Audrey Hepburn sitting barefoot in the grass, holding a young fawn in her arms, became legendary. Not because it showed a famous actress.

But because it showed tenderness at its most unscripted.

Years later, when her career slowed and she devoted herself to UNICEF, a reporter asked why she spent her life helping children ravaged by war and famine.

Audrey answered:

“I know what it’s like to be hungry. To be afraid. To be forgotten.”

The world thought she meant her childhood.

But some who knew her believed she was speaking about every creature she had ever tried to protect — children, refugees, stray animals, the small and voiceless and breakable.

Perhaps Ip was the first being she could finally save.

Perhaps that is why she kept him close.

Because love, to Audrey, was not something spoken.

It was something fed… sheltered… held.

Something that followed you through a grocery store on shaking legs

and fell asleep with its head on your shoulder.

Audrey Hepburn is remembered for many things — fashion, elegance, the little black dress, the pearl-strung smile.

But the people who loved her never spoke first of the diamonds.

They spoke of the way she knelt down to look children in the eyes.

The way she treated waiters and studio workers as equals.

The way she once stopped a rehearsal because a stray cat wandered into the room and looked hungry.

They spoke of Ip.

Because the photograph of Audrey and the fawn was not a pose.

It was the truth.

She did not shine because of the spotlight.

She shone because she never stopped guarding the smallest flickers of innocence in a world that had once tried to put them out.