When rescuers first found Suni, she was lying motionless beside her mother’s lifeless body — another victim of Africa’s brutal ivory trade. The baby elephant, barely seventeen months old, was dehydrated, wounded, and too weak to stand. Her mother had been killed for her tusks; Suni had been struck with an axe and left to die.

For days, she had tried to crawl using only her front legs, dragging herself across the dry Zambian soil in search of help. By the time the Elephant Orphanage Project team reached her, she was clinging to life.

“It was touch and go,” recalled Rachel Murton, manager of the orphanage. “We didn’t know if she would make it through the night.”

But Suni was a fighter.

After being transported to the sanctuary near Lusaka, veterinarians discovered that an axe wound had damaged her spine, leaving her right leg paralyzed. For a baby elephant, that should have been the end — elephants need all four legs to move, to play, to survive. Yet no one was willing to give up on her.

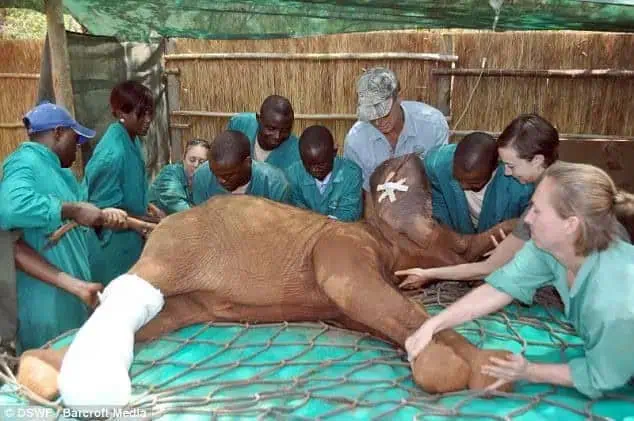

A team of specialists from Zambia, Norway, and the United States came together to give Suni a second chance.

They performed delicate surgery to relieve pressure on her spinal cord and fitted her with a custom-made aluminum brace to stabilize her leg. It was an experimental solution — no one knew if it would work.

For weeks, caregivers worked around the clock. They massaged her leg, helped her practice standing, and fed her milk every three hours. Each small step was a victory. And then, one morning, it happened — Suni took her first real step.

“The first time Suni walked on her own,” said headkeeper Kelvin Chanda, “the whole team cried. It felt like watching a child take her first steps.”

Now, with the help of her lightweight brace — built from aluminum, PVC, and leather — Suni can walk, play, and even chase after other orphaned elephants at the sanctuary.

Her joy is infectious. She trumpets loudly when her caretakers arrive, splashes in the mud, and loves to nudge her friends during feeding time.

Still, her recovery is far from over. She continues to need therapy, regular medical checkups, and help standing up after long naps.

But her progress has already become a symbol of hope — proof that compassion and science can heal even the deepest wounds.

Suni’s story also exposes the tragedy that nearly ended her life. Across Africa, elephant populations are still being decimated by poaching. Despite a worldwide ban on ivory sales since 1989, the illegal trade continues to thrive — driven largely by demand in Asia. Thousands of elephants are killed each year, their families shattered for profit.

“Every piece of ivory represents a dead elephant,” said conservationist Cynthia Moss of Kenya’s Amboseli Elephant Research Project. “The only ivory that belongs in this world is still attached to a living animal.”

Thanks to people who refused to look away, Suni survived. She stands now as both a reminder of the cruelty humanity can inflict — and of the compassion that can undo it.

When she walks across the sanctuary field, sunlight glinting off her little aluminum brace, she doesn’t just walk for herself. She walks for every elephant that didn’t get the same chance.

Because sometimes, hope comes in the shape of a small elephant learning to stand again — one step at a time.