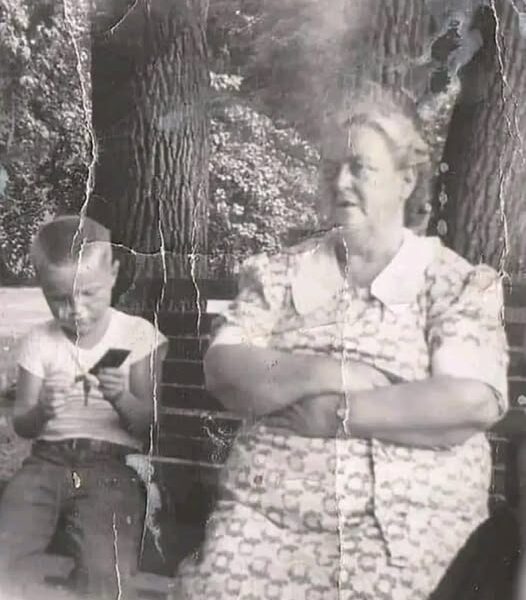

My grandmother, Grace Caldwell Bayes, was born on May 20, 1910, in a place so remote it almost doesn’t exist on a map—a stretch of eastern Kentucky known as Mud Creek, three miles south of a tiny, almost-forgotten hamlet called Tram. On the 1920 census, she was listed simply as “Gracie,” ten years old, unaware of the extraordinary life that awaited her.

By the time I stumbled into her world, she had already weathered two world wars, raised seven daughters, and carved herself out of life with a strength that could humble anyone. She was tough as an old boot, her hands calloused from years of hard work, her body worn down by arthritis, untreated diabetes, and bulging varicose veins. She had only four teeth left, yet somehow, that never slowed her down.

I spent roughly half of my childhood under her care, a period that, in my otherwise patchwork upbringing, felt like being finally, safely anchored. She looked after me with a fierce, steady love. She cared about me in a way I had rarely known, and in a childhood full of gaps and cracks, that care was priceless.

Despite her aches and her limitations, she worked the old farm barefoot, sunbaked and tireless, singing songs about Jesus and warning me, with a glint in her eye, about the devil lurking in the world. She wore a big scarf tied around her head, in a style that reminded me of a Russian peasant woman, and somehow she looked twenty years older than her age, as though the life she had lived had already carved deep lines into her face.

I would trail after her everywhere, eager to be helpful. Mostly, I was just a clumsy, overeager child trying to keep pace with her. But I did my best, willing to risk life and limb if it earned her nod of approval. We were partners in the truest sense: wandering into the fields to forage for wild greens, tending to chickens, or doing the evening chores together.

When the day wound down, we would sit on the porch, breaking green beans while the sky faded to amber. She would tell me stories of her youth, of “bad old times,” of hardship, of laughter and survival. I remember the cadence of her words, the way she wove life into narrative, teaching me that stories are the threads that bind us to one another, to the past, and to ourselves.

It is no coincidence that I am a storyteller now. I inherited her love for words, her ability to see life in stories, and her gentle yet unwavering kindness. I like to think that, like her, I am tough as an old boot. But more than that, I carry the kindness she lived by—the kindness of someone who gave her heart without hesitation, even when the world demanded everything else.

I am grown now, perhaps even old now, and yet the loss of her still slices through me. Gracie, born on Mud Creek, remains the kindest, fiercest, most enduring soul I have ever known. Everything I am, in strength, in words, and in heart, I owe to her. She is my inheritance. She is my home.

Even now, I hear her voice in the wind across a Kentucky field, see her scarf flutter in the sun, and feel her hand steadying mine. And I know that no matter how far life carries me, a part of Gracie will always be with me, guiding me, teaching me, loving me.