Once, when I was still a student at Fisk, young and eager to make my mark on the world, I set out into the hills of Tennessee to teach. It was a place where the great valley of the Mississippi begins to crumple toward the Alleghanies — a land of winding roads, rattlesnakes, and scattered cabins clinging to the sides of blue hills. There, far from railways and stage lines, life was simple, poor, and yet rich with longing.

At first, I wandered weary miles in the July sun, searching for a school that needed me. One door after another closed with the same reply: “Got a teacher already.” But then came Josie — a thin, plain girl of twenty with a dark face, quick tongue, and earnest eyes. She told me of a community “over the hill” where no teacher had come since the war, where children hungered for learning as much as they hungered for bread. Josie herself longed for schooling, though duty kept her tethered to home. In her voice I heard not complaint but determination, and it was enough to send me further still, to a small, weathered schoolhouse that once stored corn.

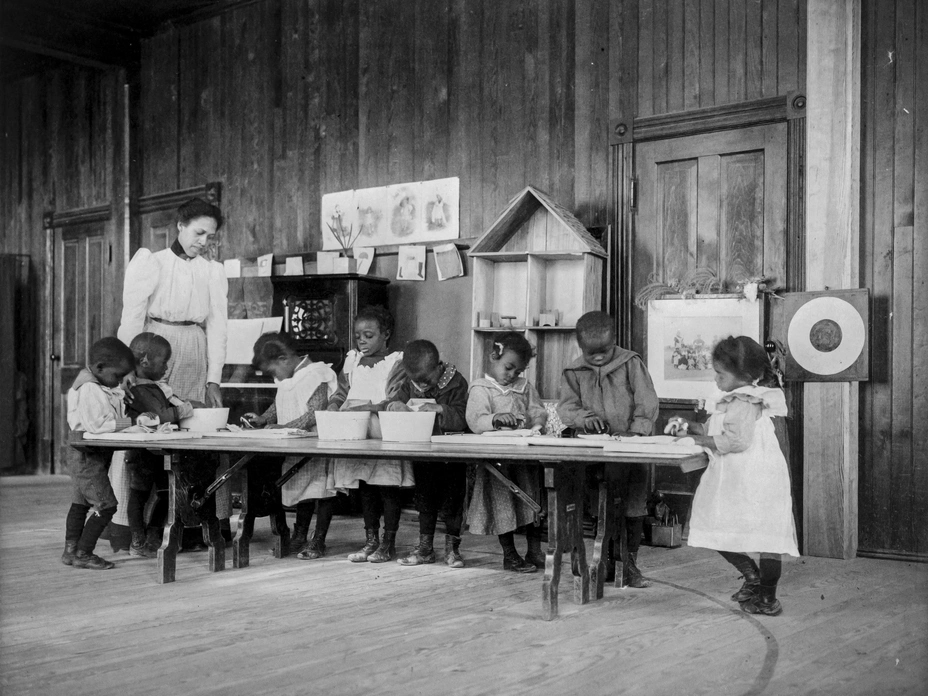

The Schoolhouse

The building was little more than a log hut, crooked and bare. Its benches were rough planks, dangerous to nap on, and the fireplace groaned as if one gust might topple it. But on that hot morning in July, nearly thirty children filed in — bare feet dusty, eyes bright with expectation, clutching Webster’s blue-back spellers as though they were treasures.

There was Josie, dogged and hopeful. Her brothers and sisters shyly followed. From nearby farms came the Dowells, the Burkes, the Lawrences, and many others — children shading in color from pale cream to deep brown, all of them carrying both hardship and hope. We read, we spelled, we sang, and I told them stories of a world beyond the hills.

Sometimes the benches emptied. Crops needed tending, or a baby needed minding. I would climb steep hills to cabins, sit by smoky hearths, and plead with parents to let their children return. Some doubted the worth of “book-learning,” but often, for a week or two, I won them back with patience and persuasion.

On Fridays, I visited homes. Some were filthy, with too many mouths and too few beds. Others were lively with laughter, fried chicken, corn pone, and songs. Best of all, I loved Josie’s porch, where peaches ripened and her mother bustled about, telling me of Josie’s wages at service — four dollars a month, too little for all the family needed. She told me of crops that failed, wells unfinished, and white neighbors who were sometimes cruel. Yet always, Josie worked and dreamed.

The Children’s World

For two summers, I taught in that valley. Sundays brought the little community together in church — Methodist or Hard-Shell Baptist — where song thundered so mightily it seemed to shake the very Veil that hung between them and opportunity.

They were bound together by poverty and grief — a burial, a birth, a marriage — and by the shared sight of the world’s indifference. Yet among them were some, like Josie and her brothers, whose young wings beat fiercely against their barriers, longing for more.

Ten Years Later

![[Young students in a classroom at the Tuskegee Normal and Industrial Institute] - PICRYL - Public Domain Media Search Engine Public Domain Search](https://cdn18.picryl.com/thumbnail/2019/11/29/young-students-in-a-classroom-at-the-tuskegee-normal-and-industrial-institute-390bea-200.jpg)

A decade passed before I returned. I was older now, and as I rode back over the familiar hills, my heart ached to see what had become of my children.

Josie was gone. Worn thin by labor and sorrow, she had given her strength to her family until she could give no more. Her gray-haired mother, eyes weary with loss, told me quietly: “We’ve had a heap of trouble since you’ve been away.”

Her brothers, John and Jim, had struggled too. Jim’s anger with life had landed him in jail, his hopes dashed against poverty and prejudice. John, loyal and awkward, had walked nine miles each day just to visit him through the bars. Together, they stole away one dark night, carrying with them Josie’s last savings.

The valley told other stories too. Some children had married, others had wandered to town, some had died too young. Families I had known were scattered, houses sold, debts unpaid. And yet — there was growth. The Burkes had added acres, though debt still weighed them down. The Dowells had bought land, married daughters, and sent sons to work.

My little log schoolhouse was gone, replaced by something larger, uglier, but sturdier — “Progress,” they called it. Children still came, spelling-books in hand, their eyes bright with the same hunger I once knew.

The Weight of It All

![African American children and teacher in classroom studying corn and cotton, Annie Davis School, near Tuskegee, Alabama] - PICRYL - Public Domain Media Search Engine Public Domain Image](https://cdn6.picryl.com/thumbnail/1904/01/01/native-jamaican-school-children-reciting-in-their-little-rough-school-house-e228d2-200.jpg)

As I walked through those hills again, joy and sorrow mingled in my chest. So many dreams had withered. So many lives had bent under the weight of poverty, prejudice, and toil. And yet, there was resilience — the stubborn fire of survival, the quiet dignity of people who kept going when the world offered them so little.

I thought of Josie, of her tired face and restless hope. She had given her youth to keep her family afloat, her dreams of school and freedom sacrificed in silence. And I wondered — how many Josies lie buried beneath the soil of this land, their lives unmarked by history, their sacrifices unseen?

How hard is the life of the lowly, and yet how deeply human, how achingly real.

As I left the valley behind, riding the Jim Crow car back to Nashville, one question pressed heavy on my heart: Was all this struggle the twilight of a fading night — or the faint light of a coming dawn?