In 2006, at Xavier High School in New York City, an English teacher named Ms. Lockwood gave her students an unusual assignment: write to a famous author and ask for advice. The students dutifully mailed out their letters, never expecting much in return. After all, authors—especially the great ones—rarely have the time to respond to fan mail, let alone to an entire class of teenagers.

But one did.

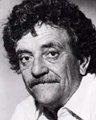

Kurt Vonnegut, then 84 years old and one of America’s most beloved novelists, took the time to write back. He had already lived his long and extraordinary life: World War II soldier, prisoner of war during the bombing of Dresden, author of Slaughterhouse-Five, Cat’s Cradle, and Breakfast of Champions. By 2006, he had stopped making public appearances. Age had left him frail, and he often described himself with his signature mix of humor and sadness as “resembling nothing so much as an iguana.”

Still, he opened his heart to a classroom of strangers. His response wasn’t long, but it contained a message so powerful that it still resonates today.

“Dear Xavier High School, and Ms. Lockwood, and Messrs Perin, McFeely, Batten, Maurer and Congiusta,” he began. “I thank you for your friendly letters. You sure know how to cheer up a really old geezer (84) in his sunset years.”

Vonnegut could have ended the letter there, a polite thank-you. Instead, he offered the students what may be the most important piece of advice he ever gave:

“Practice any art, music, singing, dancing, acting, drawing, painting, sculpting, poetry, fiction, essays, reportage—no matter how well or badly—not to get money and fame, but to experience becoming, to find out what’s inside you, to make your soul grow.”

This was the heart of his message. Success didn’t matter. Recognition didn’t matter. What mattered was the act of creation itself—the simple, joyful discipline of making something, anything, that allowed a person to grow from the inside out.

“Seriously! I mean starting right now,” Vonnegut urged. “Do art and do it for the rest of your lives. Draw a funny or nice picture of Ms. Lockwood, and give it to her. Dance home after school, and sing in the shower… Make a face in your mashed potatoes. Pretend you’re Count Dracula.”

It was whimsical, yes, but also profoundly serious. Vonnegut was trying to tell those students that art wasn’t about talent or ambition—it was about becoming more alive.

Then he gave them an assignment.

“Write a six line poem, about anything, but rhymed. No fair tennis without a net. Make it as good as you possibly can. But don’t tell anybody what you’re doing. Don’t show it or recite it to anybody, not even your girlfriend or parents or whatever, or Ms. Lockwood. OK?”

And then—tear it up. Destroy it. Scatter the pieces into trash cans far apart from one another.

Because the reward wasn’t in the applause, or the grade, or the praise. The reward was already earned in the act of creation itself.

“You will find,” Vonnegut concluded, “that you have already been gloriously rewarded for your poem. You have experienced becoming, learned a lot more about what’s inside you, and you have made your soul grow.”

Kurt Vonnegut died the following year, in 2007. That classroom assignment would be among the last pieces of public advice he ever gave. And yet it may also be one of his greatest legacies.

In a world that measures value by likes, shares, grades, and paychecks, Vonnegut reminded a handful of students—and now, millions of people who have read his letter since—that the truest reward comes not from recognition, but from the quiet act of making something for its own sake.

It is a lesson not just for writers, but for all of us: Dance, sing, draw, play, write—not because the world demands it, but because your soul does.