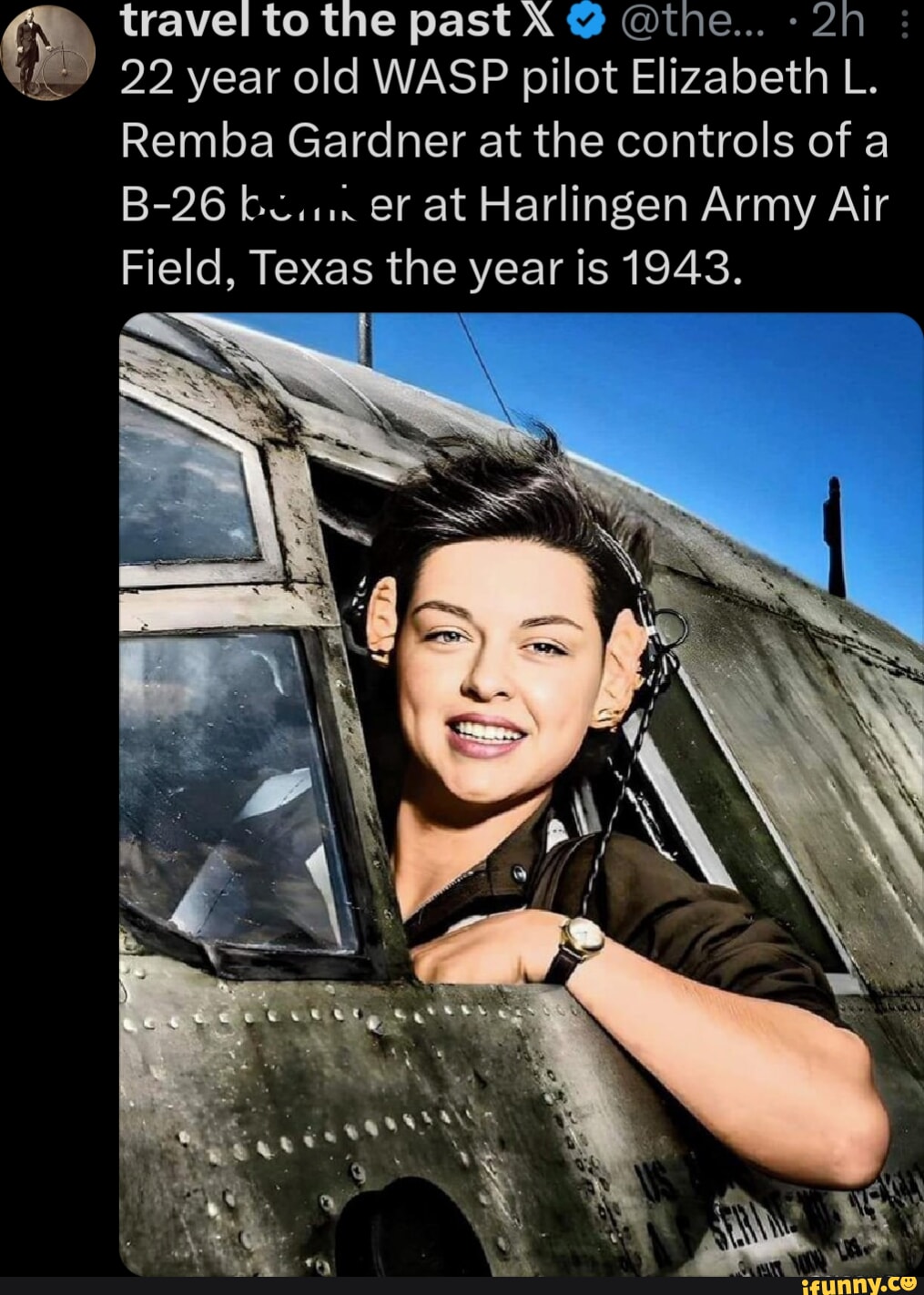

In the sepia-toned photographs of World War II, we often see the faces of young men in uniform, pilots poised at the controls of their aircraft. But every so often, a rare and powerful image breaks through those expectations—like the one taken in 1943 of a 22-year-old woman from Rockford, Illinois, confidently seated at the controls of a Martin B-26 Marauder. Her name was Elizabeth Lora Gardner—“Libby” to her friends—and she was part of an elite, groundbreaking group: the Women Airforce Service Pilots, better known as the WASP.

“The opportunity to serve in WWII was wonderful,” she told a U.S. National Archive interviewer that same year. “It has its hardships like everything else in life, but the opportunity to serve my country by flying aircraft is unimaginable and is a wonderful privilege.”

Libby wasn’t exaggerating. At a time when women in aviation were still a rarity, she had already established herself as an accomplished pilot by her early twenties. When war broke out and the U.S. military faced a desperate shortage of male pilots, the WASP program was formed, calling upon skilled women like her to step into roles that had once been unthinkable.

In October 1943, Libby completed the rigorous Women’s Flying Training program in Sweetwater, Texas. Graduating as part of Class 43-W-6, she earned her silver wings—wings that represented not just flight, but also the breaking of barriers. She was then selected for three months of transitional training in the B-26 Marauder at Dodge City Army Air Base in Kansas, mastering one of the most challenging aircraft of the war.

From there, Libby’s service took her to Harlingen Army Air Field in Texas, where she and seven fellow WASPs were assigned to the flexible gunnery school. Their mission was no small task: training gunners for combat by flying live exercises in twin-engine bombers. It was dangerous, exhausting work, but Libby embraced it with the quiet courage that defined her generation.

Her daring was not limited to the cockpit. Libby was also a member of the “Caterpillar Club”—a term reserved for those who saved their lives by parachuting out of a disabled aircraft. She earned her place after bailing out during a test with the experimental Piper Club, an almost unheard-of achievement for a woman at the time. It was a badge of honor, one that underscored both the risks she faced and her remarkable resilience.

When the war ended, the WASPs were disbanded, their contributions often overlooked in the rush to return to “normal.” But Libby did not leave the skies behind. She returned to her work as a pilot for Piper Aircraft Corporation in Pennsylvania, the same company she had worked for before the war. Flying was not just her duty—it was her calling.

In the years that followed, she built a life beyond the cockpit. She married Michael Remba, and together they had one child, Eve. Though the marriage later ended, Libby carried forward with the same independence and determination that had carried her through the war years. She eventually settled in New York, living a quieter life but never losing the spark that had defined her youth.

Elizabeth Lora Gardner passed away on December 22, 2011, at the age of 90.

Her story, like that famous photograph of her in the Marauder, is a reminder of the thousands of women who stepped forward when their country needed them most. They did not seek glory. They did not make headlines. But they flew, they served, and they sacrificed—paving the way for future generations of women in aviation and in the military.

Libby Gardner’s life was not just about flying airplanes. It was about courage, about service, and about breaking boundaries at a time when women were expected to stay grounded. She proved, quite literally, that the sky was no limit.

Thank you for your service, Libby. You were—and remain—a member of the Greatest Generation. Lest we forget.