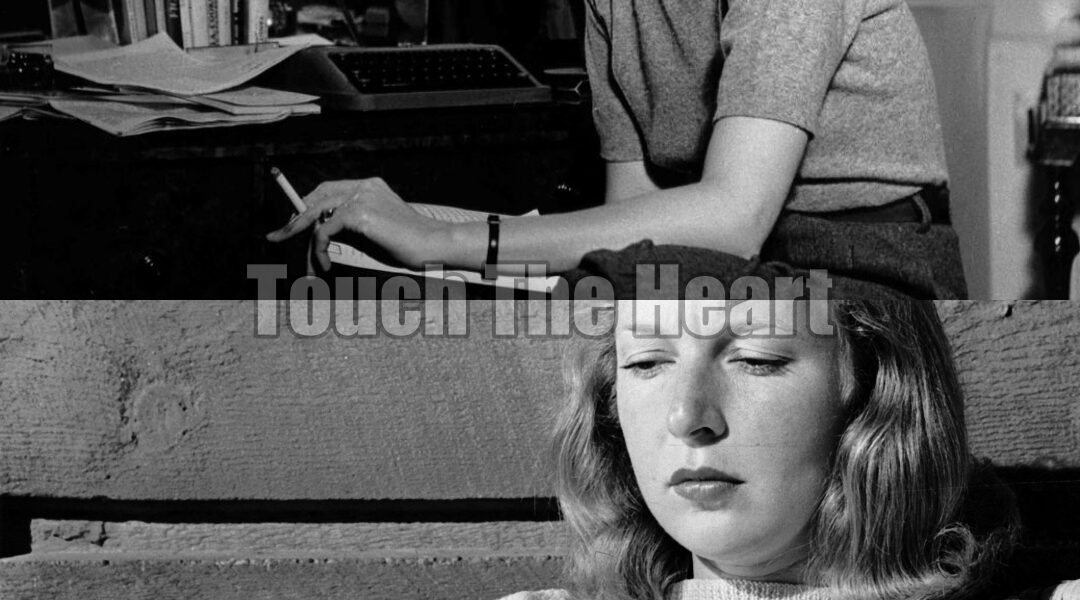

She was never meant to be there.

War had rules, and one of them was clear: women did not go ashore on D-Day. They could report from London, type from hotel rooms, listen to rumors in cafés. They could interview pilots, generals, recovering soldiers — but not storm the beaches of Normandy.

Martha Gellhorn had spent years watching men go where history happened while she was expected to record the aftermath. She had crossed continents to write about the forgotten, the starving, the displaced, the wounded — and still, when the biggest story of the century approached, she was told to stay behind.

Her husband, Ernest Hemingway — the most famous war correspondent in the world — had been given his press pass without question.

She was denied.

That was the moment something inside Martha hardened, not with rage, but with certainty.

If they would not let her witness history, she would have to break into it.

The Night Before

It was June 5, 1944 — the eve of the greatest amphibious invasion in human history. Reporters swarmed the docks like restless birds, all hoping to get a spot on a ship. Martha walked among them with a calm that hid the storm inside her.

She spotted a hospital barge. Not glamorous. Not meant for press. Not meant for her.

Perfect.

She flashed her press credentials, smiled, and said she was there to interview “medical personnel about treatment logistics.” The guards barely looked up — the invasion consumed every mind and every hand. She walked aboard.

But she was not there to interview anyone.

She found a small bathroom, slipped inside, and locked the door. It was dark. Damp. Reeking of disinfectant and diesel. She sat on the floor with her back against the metal wall and listened to the boat creak against the tide.

Then came the seasickness.

She vomited until her throat burned. She curled onto the cold tile and tried not to think about the fact that she was utterly alone, that she had lied her way into a war, and that there was no turning back.

But beneath the nausea and fear, something steadier held her upright:

She was exactly where she needed to be.

The Dawn of D-Day

At first light, she unlocked the door and stepped into the open air.

And the world was no longer the world.

The horizon was filled — not with water, but with war. Thousands of ships, stretching farther than the eye could see. Battleships, destroyers, troop carriers, landing craft — an iron armada cutting through the sea.

Overhead, planes roared like thunder tearing the sky apart. Bombs fell in the distance. The coastline of France exploded with fire.

She had imagined it before — every journalist had — but nothing could prepare her for the sight of history before it became history. This wasn’t a news event. It was the world changing in real time.

She wasn’t taking notes.

She wasn’t writing metaphors.

She was watching death arrive in waves.

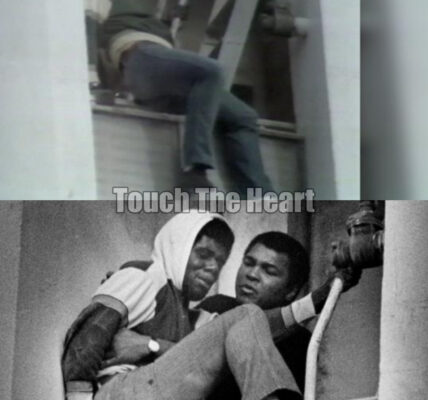

Then she heard it — not the roar of engines, not the crash of shells, but something human.

Screaming.

The sea was filling with wounded men. Bodies floated between boats, some alive, some broken, some already swallowed by the tide. The medics around her sprang into motion.

And Martha moved with them.

She grabbed bandages. She lifted stretchers. She held hands slick with blood. She whispered words no reporter had ever been trained to say:

“You’re going to make it.”

“Stay with me.”

“You’re not alone.”

In that moment, she wasn’t a correspondent.

She was a witness with her whole body.

Omaha Beach

By nightfall, Martha was soaked, blistered, shaking with exhaustion — but she refused to stay on the boat. She followed the medics ashore, wading through freezing water toward Omaha Beach.

The sand was not sand.

It was churned earth, metal shards, shell craters, broken weapons, and bodies — so many bodies the waves could not claim them fast enough.

She carried stretchers through surf that tried to pull them down. Her palms split open. Her arms trembled. She could no longer feel her feet.

But she kept moving.

She had come for a story — and instead stepped into a hell where no sentence could ever carry enough weight.

She saw boys — not men, not soldiers, but boys — calling for mothers who would never hear them again. She saw medics who hadn’t slept in days, performing surgery in the sand beneath gunfire. She saw officers break apart inside their own orders.

And she worked beside them until her strength was gone.

By the time she finally collapsed on the beach, the moon was rising over a shore that had cost more than any victory ever could.

The Price of Witnessing

In the days that followed, Martha did what she always did:

She wrote.

Not about glory. Not about strategy. Not about flags raised in triumph.

She wrote about blood in the surf.

She wrote about boys too young to shave.

She wrote about hands she held as they went still.

Her reporting was raw, unromantic, unfiltered. It was not the kind of story generals wanted the world to read.

But it was the truth.

She wrote as someone who had been there — not as a spectator, but as a survivor.

After the War

For sneaking onto the invasion, Martha was not celebrated.

She was arrested, stripped of her press credentials, and banned from further military reporting.

It didn’t matter.

Because something had shifted forever.

She no longer believed that journalists were meant to simply observe. She believed they were meant to stand where no one else would stand, so that the forgotten would not vanish from history.

She would go on to report wars for decades — Vietnam, Panama, El Salvador — always choosing the front lines, never the safe hotel balcony.

And when she was finally too old to walk battlefields, she refused the quiet life. She spent her last years helping refugees, writing letters for those who couldn’t write their own, lifting voices that no newspaper wanted to hear.

She died in 1998, not rich, not pampered, not widely honored.

But free.

Because she had lived on her own terms, in a world that tried to cage her at every turn.

Why Her Story Matters

History remembers the generals.

Statues remember the heroes.

Photos remember the soldiers.

But Martha Gellhorn carried the stories of the forgotten — and became a legend not because she was fearless…

…but because she refused to look away.

She was the only woman to land on D-Day.

Not by permission.

But by courage.

And in the end, that is the legacy she left:

Sometimes the door to history is locked.

Sometimes the only way in…

…is to break it open.